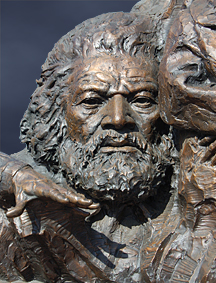

Frederick Douglass

1818-1895

History and Heart

Famed abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison penned the opening preface to Frederick Douglass’ Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, An American Slave. Just following Garrison’s preface, before Douglass’ text begins, is a letter to Douglass from Wendell Phillips, Esq., a member of the nineteenth-century Massachusetts Anti-Slavery Society. His letter begins as follows: “My Dear Friend: You remember the old fable of ‘The Man and the Lion,’ where the lion complained that he should not be so misrepresented ‘when the lion wrote history.’ I am glad the time has come when the ‘lions write history.’ Frederick Douglass was a lion indeed.

Born into slavery in 1818, his mother was a slave, and his father, a white man – a slaveholder. Douglass lived in slavery for 20 years before he was finally able to escape to the North, and ultimately become the foremost African-American in nineteenth-century public life. Douglass was a remarkable man, who managed to find a way to teach himself how to read and write while enslaved. His courage, intellect and brilliant articulateness paved the way for more “lions” to write history – for other freedmen and women to reveal the truth about the American slave system and display the realities of nineteenth-century America. Furthermore, slave narratives like Douglass’ “not only offered testimony to the cruelties of American slavery but also gave warrant that Afro-Americans possessed the higher intellectual powers granted to all human beings.”

Douglass certainly had similar intentions in mind when he wrote not one, but three autobiographical works. In his Appendix to Narrative he concludes: “Sincerely and earnestly hoping that this little book may do something toward throwing light on the American slave system, and hastening the glad day of deliverance to the millions of my brethren in bonds – faithfully relying upon the power of truth, love, and justice, for the success in my humble efforts – and solemnly pledging my self anew to the sacred cause, – I subscribe myself, Frederick Douglass. Lynn, Mass., April 28, 1845.”

Frederick Douglass held all slaves in his heart when he set out to achieve his manifold accomplishments. He sought his feats not only to liberate himself from an inhumane system, but ultimately to defeat the system entirely, and to see his people walk tall and proud and free in the country they’d come to call home.

Biography in Brief

It is said that “Frederick Douglass looked so much like a President that one day in the White House a visiting judge mistook him for Abraham Lincoln. Douglass’ skin was a middling brown color, and he was never bashful about his mixed parentage. ‘The son of a slaveholder stands before you, by a colored mother,’ he told a New York audience.” Douglass did not know much about his background: “I was born in Tuckahoe, near Hillsborough, and about twelve miles from Easton, in Talbot County, Maryland. I have no accurate knowledge of my age, never having seen any authentic record containing it...I do not remember to have ever met a slave who could tell of his birthday.” Even his parents were elusive figures in his life: “My mother was named Harriet Bailey. She was the daughter of Isaac and Betsey Bailey, both colored, and quite dark….” “My father was a white man...The opinion was also whispered that my master was my father; but of the correctness of this opinion, I know nothing.” And even though he knew his mother’s name and immediate ancestry, he knew little else: “I never saw my mother, to know her as such, more than four or five times in my life... She made her journeys to see me in the night, traveling the whole distance on foot, after the performance of her day’s work. She was a field hand, and a whipping is the penalty of not being in the field at sunrise...”

As his Narrative reveals, Douglass was truly a man of integrity and wisdom. Though he grew up in the blight of slavery, he evolved into a man who sought equity and fairness in all situations, from the Civil War to his own relationships. Like his mother and father, he wound up in an interracial relationship, although his was indeed consensual, while the former was certainly not. In fact, his was likely the first publicly recognized interracial marriage:

“Douglass’ wife for 44 years was a free Negro woman he met while he was still a slave in Baltimore. Two years after she died in 1882, he married a white woman, Helen Pitts, who had been his secretary. This brought him a storm of criticism from both blacks and whites. In reply, Douglass sought to give an exact definition of his feelings about color and race. “The fundamental and everlasting objection to slavery is not that it sinks a Negro to the condition of a brute, but that it sinks a man to that condition,’ he wrote. ‘I base no man’s right upon his color and plead no man’s rights because of his color. My interest in any man is objectively in his manhood and subjectively in my own manhood.”

Such displays of his sense of justice and character were not limited to the United States. Douglass left for England after his first book was published, out of well-warranted fear that he would be caught and sent back to his master. He gave lauded lectures in England, Scotland, and Ireland for two years, until Ellen and Alan Richardson, a British couple, bought his freedom for seven hundred dollars. Upon his return to America, he served as president of the ill-fated Freedman’s Savings Bank, marshal of the District of Columbia, recorder of deeds for the District of Columbia, minister-resident and consul-general to the Republic of Haiti, and charge d’affaires for Santo Domingo – all a far cry from working the fields from dawn ‘til dusk.

Douglass also became well-acquainted with Abraham Lincoln, such that they conferred with one another during the Civil War. Douglass gave Lincoln insight and guidance with regard to the seemingly doomed issue of slavery and the South, and even recruited African Americans to the Union Army. He was considered to be “the unofficial president of American Negroes in the years before and immediately after the Civil War.”

Douglass’ Chilling Recollections of Slavery

But, before all of this marked distinction and honor, Douglass experienced the worst of the American slave system. Here are just a few of his many recollections on his experience as a slave:

“I have often been awakened at the dawn of day by the most heart-rending shrieks of an own aunt of mine, whom he used to tie up to a joist, and whip upon her naked back till she was literally covered with blood. No words, no tears, no prayers, from his gory victim, seemed to move his iron heart from its bloody purpose. The louder she screamed, the harder he whipped; and where the blood ran fastest, there he whipped longest…. I remember the first time I witnessed this horrible exhibition…. I never shall forget it whilst I remember anything. It was the first of a long series of such outrages, of which I was doomed to be a witness and a participant... It was the blood-stained gate, the entrance to the hell of slavery, through which I was about to pass.”

“In hottest summer and coldest winter I was kept almost in a state of nudity…. I slept generally in a little closet, without even a blanket to cover me. In very cold weather I sometimes got down the bag in which corn was carried to the mill, and crawled into that…. My feet have been so cracked with the frost that the pen with which I am writing might be laid in the gashes.”

“Mr. Covey succeeded in breaking me. I was broken in body, soul, and spirit. My natural elasticity was crushed, my intellect languished, the disposition to read departed, the cheerful spark that lingered about my eye died; the dark night of slavery closed in upon me; and behold a man transformed into a brute!”

However, Douglass’ overcame this state of hopelessness and futility after getting into a fierce fight with his master, who was Mr. Covey at the time:

“This battle with Mr. Covey was the turning-point in my career as a slave.... It rekindled the few expiring embers of freedom, and revived within me a sense of my own manhood.... I felt as I had never felt before. It was a glorious resurrection, from the tomb of slavery, to the heaven of freedom.... I now resolved that, however long I might remain a slave in form, the day had passed forever when I could be a slave in fact. I did not hesitate to let it be known of me, that the white man who expected to succeed in whipping, must also succeed in killing me...From this time I was never again what might be called fairly whipped, though I remained a slave four years afterwards. I had several fights, but was never whipped.”

Douglass’ line, “I now resolved that, however long I might remain a slave in form, the day had passed forever when I could be a slave in fact,” is famous amongst contemporary scholars of history and social studies. It denotes a distinction between physical and psychological enslavement, and for Douglass, standing up to his master, both psychologically and physically, in this fight helped disentangle him from the psychological bonds of slavery. Nevertheless, he had yet to be “free in form,” and it was reading and writing that pushed him closer and closer to freedom, in all senses of the term.

Reading and Writing

Douglass was introduced to literature before working for Mr. Covey. His former masters were Mr. And Mrs. Auld, and she took an initially soft, warm stance towards young Douglass. She set about teaching him his A, B, Cs, and he was thrilled to learn. However, it did not take long before Mr. Auld put a stop to such behavior. He reprimanded his wife in front of Douglass: “If you give a nigger an inch, he will take an ell. A nigger should know nothing but to obey his master – to do as he is told to do. Learning would spoil the best nigger in the world.” These words sunk deep into Douglass’ heart and took on great importance:

“It was a new and special revelation, explaining dark and mysterious things, with which my youthful understanding had struggled, but struggled in vain...It was a grand achievement, and I prized it highly. From that moment, I understood the pathway from slavery to freedom...Though conscious of the difficulty of learning without a teacher, I set out with high hope, and a fixed purpose, at whatever cost of trouble, to learn how to read.”

Interestingly, he wound up learning how to write before learning how to read. And his tactics were clever:

“...when I met with any boy who I knew could write, I would tell him I could write as well as he. The next word would be, “I don’t believe you. Let me see you try it.” I would then make the letters which I had been so fortunate as to learn, and ask him to beat that. In this way I got a good many lessons in writing, which it is quite possible I should never have gotten in any other way.”

He also took advantage of his young Master Thomas’ schooling:

“…my little Master Thomas had gone to school, and learned to write, and had written over a number of copybooks…. My mistress used to go to class meeting at the Wilk Street meetinghouse every Monday afternoon, and leave me to take care of the house. When left thus, I used to spend the time in writing in the spaces left in Master Thomas’s copy-book, copying what he had written. I continued to do this until I could write a hand very similar to that of Master Thomas. Thus, after a long, tedious effort for years, I finally succeeded in learning how to write.”

Consistent with his boundless compassion, he began to teach other slaves to read and write as soon as he was able: “This desire [to read] soon sprang up in the others also. They very soon mustered up some old spelling-books, and nothing would do but that I must keep a Sabbath school. I agreed to do so, and accordingly devoted my Sundays to teaching these my loved fellow-slaves how to read.”

The task was not easy; there was great risk involved:

“Every moment they spent in that school, they were liable to be taken up, and given thirty-nine lashes. They came because they wished to learn. Their minds had been starved by their cruel masters. They had been shut up in mental darkness. I taught them because it was the delight of my soul to be doing something that looked like bettering the condition of my race. I kept up my school nearly the whole year...and, beside my Sabbath school, I devoted three evenings in the week...to teaching the slaves at home. And I have the happiness to know, that several of those who came to Sabbath school learned how to read…”

Free in Form and Fact

In 1838, after several failed attempts, Douglass finally managed to escape to freedom in the North and settled in Massachusetts where he came under the tutelage of abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison. He traveled with other brave souls seeking freedom, and of course, their journey was quite dangerous:

“Our path [to freedom] was beset with the greatest obstacles; and if we succeeded in gaining the end of it, our right to be free was yet questionable–we were yet liable to be returned to bondage.... … As the time drew near for our departure, our anxiety became more and more intense. It was truly a matter of life and death with us. The strength of our determination was about to be fully tested.”

Douglass writes that the most arduous part of the expedition was being forced to leave his friends. They separated before reaching freedom together, however, Douglass pressed on: “The wretchedness of slavery, and the blessedness of freedom, were perpetually before me…. I remained firm, and, according to my resolution, on the third day of September, 1838, I left my chains, and succeeded in reaching New York without the slightest interruption of any kind.”

He goes on to say: “I have been frequently asked how I felt when I found myself in a free State. I have never been able to answer that question with any satisfaction to myself. It was a moment of the highest excitement I ever experienced. I suppose I felt as one may imagine the unarmed mariner to feel when he is rescued by a friendly man-of-war from the pursuit of a pirate.”

To be free in form and fact was something Douglass had dreamed of his whole life. But despite his initial ecstasy, sorrow slowly crept back into his being… For Douglass’ compassion and will for freedom for his people, and his desire for equality for all men and women (which he ultimately acted upon by uniting with Susan B. Anthony), rose above all else. Douglass’ eternal drive and limitless heart are evident throughout the pages of his works, and one particular quote from Narrative conveys both quite clearly:

“...my fellow-slaves...were noble souls; they not only possessed loving hearts, but brave ones. We were linked and interlinked with each other. I loved them with a love stronger than any thing I have experienced since. It is sometimes said that we slaves do not love and confide in each other. In answer to this assertion, I can say, I never loved any or confided in any people more than my fellow-slaves...I believe we would have died for each other...We never moved separately. We were one...”

“What to the Slave on the Fourth of July?” by Frederick Douglass

http://www.infoplease.com/t/hist/slave-on-fourth/

Frederick Douglass and Houston A. Baker, Jr. ed., Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave (New York: Penguin Classics, 1982) 43.

Roger Butterfield, “The Search for a Black Past,” Life Magazine, Vol. 65. No. 21, November 22, 1968, 102.