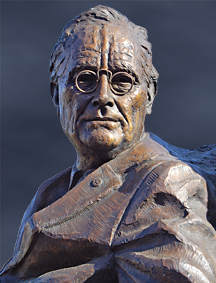

Franklin Delano Roosevelt

1882-1945

From Patrician to Politician

Franklin Delano Roosevelt was born on January 30, 1882. He went on to become the 32nd President of the United States (1933-1945) through two critical periods in American history: the Great Depression and World War II. FDR was inspired by his distant cousin Theodore Roosevelt, a man who cared about other people and wanted to leave the world better than he found it. Like Teddy Roosevelt, FDR decided to serve his country as an elected official. In her deeply engaging textbook, Freedom: A History of Us, Joy Hakim wrote of FDR: “This patrician gentleman took the nation from depression through world war, with dignity, courage and unfailing wit and confidence. Never pretending to be anything other than he truly was, he made Americans everywhere feel that they were family.” Winston Churchill, former prime minister of the United Kingdom who worked quite closely with Roosevelt, once said, “Meeting [FDR] was like uncorking a bottle of champagne.”

FDR’s storybook-like childhood did not predestine him to be one of the greatest democratic leaders of all time, however, his father was a democrat, despite his republican family, and as stated, FDR was indeed influenced by his predecessor, Teddy Roosevelt. Franklin Roosevelt grew up on an estate on the banks of the Hudson River in Hyde Park, New York. His family was wealthy and often involved in civic engagement. Franklin’s father even introduced him to President Grover Cleveland when little Franklin was just five years old.

Doris Kearns Goodwin, historian and author of the great work No Ordinary Time: Franklin and Eleanor Roosevelt: The Home Front in World War II, stated once in an article for Time Magazine:

No factor was more important to Roosevelt’s success than his confidence in himself and his unshakable belief in the American people. What is more, he had a remarkable capacity to transmit his cheerful strength to others, to make them believe that if they pulled together, everything would turn out all right. The source of this remarkable confidence can be traced back to his earliest days. “All that is in me goes back to the Hudson,” Roosevelt liked to say, meaning not simply the peaceful, slow-moving river and the big, comfortable clapboard house but the ambiance of boundless devotion that encompassed him as a child. Growing up in an atmosphere in which affection and respect were plentiful, where the discipline was fair and loving, and the opportunities for self-expression were abundant, he came to trust that the world was basically a friendly and agreeable place.

FDR carried this confidence and sense of justice out into the world with him. These qualities affected his behavior and decisions as a leader, from his friendly and inclusive Fireside Chats to his swift ability to maneuver the difficult challenges faced by a country in times of great turbulence.

FDR finally left Hyde Park to attend Harvard University and then Colombia Law School, as his parents had expected of him. While at Harvard, Roosevelt wrote to segregated colleges in the South, appealing to them to accept African American students. Former president Bill Clinton lauds Roosevelt’s “politics of inclusion,” which were evident in his collegiate civic action. Clinton wrote:

As a state legislator, Governor, and President, Roosevelt pioneered the politics of inclusion. He built a broad, lasting, national coalition uniting different regions, different classes and different races. He identified with the aspirations of immigrants, farmers and factory workers – “the forgotten Americans,” as he called them. He considered them citizens just as fully as he was.

Roosevelt’s “politics of inclusion” were only amplified by his equally politically charged wife, Eleanor, who was a champion for humanity in her own right. The two of them raised five children together. FDR was an energetic, upbeat father, who loved to sail, ride horses and hike. Though their marriage was not always easy, when FDR fell ill with polio, Eleanor became his legs, traveling across the country to meet with citizens and relay firsthand accounts of the state of the nation to her husband. She was a tremendous source of support for him, and the two formed one of the most successful political partnerships in American history.

Breaking the Mold: A Paraplegic President

In 1921 at age 39, Franklin Roosevelt suffered a severe attack of polio that left him crippled for life. With determination and courage he endured painful therapy and regained the use of his upper body, but he would never walk again without heavy braces and the help of his aids. The attack was sudden. He went to bed one evening, not feeling well, and woke up the next morning completely paralyzed.

In her Time Magazine article, Doris Kearns Goodwin wrote:

He was 39, at the height of his powers, when he became a paraplegic. He had been an athlete, a man who had loved to swim and sail, to play tennis and golf, to run in the woods and ride horseback in the fields. Determined to overcome his disability, he devoted seven years of his life to grueling physical therapy. In 1928, however, when he accepted the Democratic nomination for Governor of New York, he understood that victory would bring an end to his daily therapy, that he would never walk under his own power again.

This physical loss indeed put Roosevelt’s sense of confidence to the test. But, as writer Lorenzo Milam so aptly put it: “He was brave, that Roosevelt. O Lordy he was brave. A clear-cut nothing-from-the-waist-down case, yet he forced himself to walk. With steel and fire he kept pouring his will into what was left of his muscles, trying to walk that walk again.”

He never did walk the same way again, but his physical handicap hardly impeded his leadership abilities; if anything, the experience bolstered his capacity for compassion and patience, both important qualities for a great leader – especially one elected as president for four terms in a row.

Interestingly, the public never knew how physically handicapped he was. Photographers never published photos that revealed his braces, wheelchair, or aids. His political career may have progressed quite differently had the public been more aware of his disability. He may have been highly judged, even scorned, and the American people may have lost faith in him; for physical disability was not well understood or accepted in the early twentieth century. Helen Keller’s life story is an excellent example of overcoming such intolerance. She too lived through the Great Depression and World War II. She even met President Roosevelt, and as one of her biographer’s wrote, she “could not realize that he was being wheeled up to the speaker’s table.” Rather, Keller said she “‘sensed his powerful spirit striding among us.’ In her mind’s eye, she saw him ‘not in his wheel-chair but walking out with archangel might.’”

Roosevelt’s might certainly outlasted his physical abilities, and again, was perhaps strengthened by his struggle with polio. In the same Time Magazine article, Goodwin continued:

After what his wife Eleanor called his trial by fire, he seemed less arrogant, less superficial, more focused, more complex, more interesting. “There had been a plowing up of his nature,” Labor Secretary Frances Perkins observed. “The man emerged completely warmhearted, with new humility of spirit and a firmer understanding of philosophical concepts.” He had always taken great pleasure in people. But now, far more intensely than before, he reached out to know them, to pick up their emotions, to put himself in their shoes. No longer belonging to his old world in the same way, he came to empathize with the poor and the underprivileged, with people to whom fate had dealt a difficult hand.”

So, after seven tough years of physical therapy, Roosevelt entered back into politics as governor of New York. Five years later, on March 4, 1933, he delivered his inaugural address in front of the White House, perhaps more ready for the presidency than ever before. His first task as President of the United States: pull the country out of a great depression.

The Great Depression

In the months before Roosevelt took office the US economy was growing more and more bleak. Banks were closing down and the government was uncertain whether they would be able to make payroll. Many experts said that capitalism was “too sick” to recover. President Hoover said, “We are at the end of our string. There is nothing more we can do.” In a speech celebrating the three-year anniversary of the Social Security Act, FDR recalled the ghastly circumstances of the depression:

“…millions of our people were living in wastelands of want and fear. Men and women too old and infirm to work lived their remaining years within the walls of a poorhouse. Fatherless children early learned the meaning of being a burden to relatives or to the community. Men and women, still strong, still young, but discarded as gainful workers, were drained of self-confidence and self-respect.”

In spite of these dire circumstances, and in stark contrast to Hoover’s hopeless sentiment, FDR not only managed to instill confidence in his weary nation, but he created policies that began to tangibly revive the economic state of the country.

His administration created the famous “New Deal” programs. The New Deal included: the Emergency Banking Act, which restored public confidence in banks; the Civilian Conservation Corps, which put unemployed young men to work; Social Security, which provided unemployment and retirement benefits to the elderly; the Works Progress Administration, or WPA, which simultaneously created work for the unemployed (especially women) and improved social services and infrastructure; and more. FDR and his administration also put an end to most child labor within the United States, regulated the stock market, helped guarantee fair wages, encouraged unions, limited work hours, and brought electricity to rural areas. Not too shabby for a newly elected president.

One might assume that FDR was praised and appreciated by all Americans during his presidency. This was not the case. By some, he was called “a traitor to his class”. During the decade leading up to his presidency, the “Roaring Twenties”, the federal government’s main priority was to grow American business and industry; it had little interest in investing in its people. FDR, on the other hand, used government money to aid workers, farmers and the needy. To some, this represented a rejection of the aristocratic society into which he was born. FDR sought to spread wealth, rather than confine it to a limited elite.

This was his message from day one. His aim was to unite Americans in the common cause of strengthening and uplifting their country. His tremendous ability to do just that was made quite evident in his first inaugural speech. On March 4, 1933, standing in the famed East Portico of the Capitol Building, and being broadcast to millions of Americans across the country, FDR declared:

“This is pre-eminently the time to speak the truth, the whole truth, frankly and boldly. Nor need we shrink from honestly facing conditions in our country today. This great nation will endure as it has endured, will revive and will prosper. So first of all let me assert my firm belief that the only thing we have to fear is fear itself.”

Americans were heartened by FDR’s bold and sincere honesty. It truly was Roosevelt’s “lasting accomplishment,” as Doris Kearns Goodwin stated, “that he found a middle ground between the unbridled laissez-faire of the ‘20s and the brutal dictatorships of the ‘30s.” She continues:

His conviction that a democratic government had a responsibility to help Americans in distress – not as a matter of charity but as a matter of social duty – provided a moral compass to guide both his words and his actions. Believing there had never been a time other than the Civil War when democratic institutions had been in such jeopardy, Roosevelt…fundamentally altered the relationship of the government to its people, rearranged the balance of power between capital and labor and made the industrial system more humane.

FDR’s stalwart commitment to the greater welfare of the American people remained consistent throughout his twelve-year presidency. In his second inaugural address, he professed, “The test of our progress is not whether we add more to the abundance of those who have much; it is whether we provide enough for those who have too little.” His desire to continue to provide for the most needy Americans was challenged however, when, in 1941, he was faced with the great decision of whether or not to join the British and the Russians in their fight against Hitler’s inhumane stranglehold of Europe in what would become the Second World War.

The Home Front vs. The War Front

WWII was well underway by 1939, but it wasn’t until 1941 that the United States joined the Allies. There is much criticism of FDR’s initial resistance to join the war, especially in light of the rampant brutality of the Nazis. However, Roosevelt had just spent six years repairing a very weak nation. The U.S. was finally beginning to thrive again, and participating in a war would divert resources towards its military, which would need to be built up if they were to go to war, and ultimately compromise the country’s newfound health and wellbeing. Furthermore, as a democratic leader, FDR was torn between two very vocal constituencies known as the “isolationists” and the “interventionists”. The isolationists believed that the Pacific and Atlantic oceans provided some sort of buffer between the U.S. and the rest of the world. They felt that America would be better off staying out of the war, and some were staunchly against war on moral principle. The interventionists, on the other hand, recognized the growing reality that the Allied forces could not withstand Nazi power alone, and felt that America had an obligation to join the Allied cause. They urged the President to take action.

The President was acutely aware of the rising tension between domestic and international needs. In the early stages of the international conflict, FDR addressed his people in his “Quarantine of War-Seeking Powers” speech in Chicago in October of 1937:

“On my trip across the continent and back I have been shown many evidences of the result of common sense cooperation between municipalities and the Federal Government and I have been greeted by tens of thousands of Americans who have told me in every look and word that their material and spiritual well-being has made great strides forward in the past few years.

And yet, as I have seen with my own eyes, the prosperous farms, the thriving factories and the busy railroads, as I have seen the happiness and security and peace which covers our wide land, almost inevitably I have been compelled to contrast our peace with very different scenes being enacted in other parts of the world.”

Nevertheless, he concluded:

“It is my determination to pursue a policy of peace. It is my determination to adopt every practicable measure to avoid involvement in war. It ought to be inconceivable that in this modern era and in the face of experience, any nation could be so foolish and ruthless as to run the risk of plunging the whole world into war by invading and violating, in contravention of solemn treaties, the territory of other nations…Yet the peace of the world and the welfare and security of every nation, including our own, is today being threatened by that very thing.”

FDR kept the war front at bay for the next four years. He participated indirectly with the Lend-Lease Act, an agreement between the United States and the Allied forces stating that the U.S. would supply the Allies with war materials, but Roosevelt did not aggressively take on his role as Commander in Chief until December 7, 1941, “a date,” he said, “which will live in infamy.”

Pearl Harbor

In 1941 the U.S. Pacific Fleet was headquartered at Pearl Harbor in Hawaii. On December 7, 1941 Japanese planes dropped bombs on the harbor’s Battleship Row. The warships were docked in neat lines – an easy target. The attack sank nearly 200 ships; 2,000 people were found dead.

The Pearl Harbor attacks abolished any last notion of isolationism. On December 7, Roosevelt asked Congress to declare war on Japan. Three days later Japan’s allies, Germany and Italy, declared war on the Unites States.

In the next four years, as Commander in Chief of the armed forces, FDR made vital strategic decisions, worked closely with British Prime Minister Winston Churchill, and selected an extraordinary team of generals and admirals.

Fireside Chats

One way in which Roosevelt was able to maintain the faith and trust of his people at such a fearful time was through his beloved “fireside chats,” live radio broadcasts across the U.S. FDR was a fine speaker. He used his skill to connect to the American people. He knew how to communicate the complicated, often overwhelming challenges the U.S. faced during his four-term presidency. He used simple language that was easy to relate to. He even instructed people to spread maps out before them while listening to his talks to help them better connect to his speeches. On February 9, 1942 he spoke to his nation about the war:

“We are now in the midst of a war, not for conquest, not for vengeance, but for a world in which this nation, and all that this nation represents, will be safe for our children…. We are going to win the war and we are going to win the peace that follows.”

His fireside chats better enabled Roosevelt to reassure Americans that he was doing everything in his power to end the great war.

The Legacy of Franklin Delano Roosevelt

Months before Pearl Harbor, months before the U.S. joined the war, FDR addressed his nation in the 1941 State of the Union. He said:

In the future days, which we seek to make secure, we look forward to a world founded upon four essential freedoms. The first is freedom of speech and expression – everywhere in the world. The second is freedom of every person to worship God in his own way – everywhere in the world. The third is freedom from want.... The fourth is freedom from fear.”

These are the values he wanted to see carried out in his lifetime. They are values that women and men, young and old, still fight for today. FDR envisioned a world of mindful democracy based upon a common sense of equality and justice. He set out to create the United Nations in order to uphold these values and to translate their sentiment into just action. He did not live to see the U.N. come to fruition, but he did, with the help of Stalin and Churchill, lay the foundation for this apparatus of global security.

In her Time magazine article, Goodwin writes of Roosevelt’s aims during the end of his life:

As the tide of war began to turn decisively, in the year before his death, Roosevelt began to put in place the elements of his vision for the world that would follow the titanic conflict. It was to be a world in which all peoples were entitled to govern themselves. With this aim, he foresaw and worked toward the end of the colonial imperialism that had dominated much of the globe. Through the U.N., which he was instrumental in establishing, we would, he hoped finally have an international structure that could help keep the peace among the nations…. Today, more than a half-century after his death, Roosevelt’s vision, still unfulfilled, still endangered, remains the guardian spirit for the noblest and most humane impulses of mankind.

In another article for Time, American historian Arthur Schlesinger Jr. took on a similar optimistic view of FDR’s legacy:

Take a look at our present world. It is manifestly not Adolf Hitler’s world. His Thousand-Year Reich turned out to have a brief and bloody run of a dozen years. It is manifestly not Joseph Stalin’s world. That ghastly world self-destructed before our eyes. Nor is it Winston Churchill’s world. Empire and its glories have long since vanished into history. The world we live in today is Franklin Roosevelt’s world. Of the figures who for good or evil dominated the planet 60 years ago, he would be least surprised by the shape of things at the millennium. And confident as he was of the power and vitality of democracy, he would welcome the challenges posed by the century to come.

Goodwin’s article elaborates upon FDR’s leadership in democracy, arguing that, “His example strengthened democracy everywhere.” She then quotes British philosopher Isaiah Berlin: “He became a legendary hero,” stated Berlin, “Peoples far beyond the frontiers of the U.S. rightly looked to him as the most genuine and unswerving spokesman of democracy. He had all the character and energy and skill of the dictators, and he was on our side.’”

FDR’s death was tragic and sudden. By April of 1945, Roosevelt was exhausted by the war effort. He took a trip to Warm Springs, Georgia, his favorite retreat center for physical therapy. He went there to relax, and to get some presidential work done in a peaceful environment.

On April 12, 1945, Roosevelt was sitting for a portrait by Elizabeth Shoumatoff when he suddenly said, “I have a terrific pain in the back of my head,” and slumped forward, unconscious. His doctor at the time, Dr. Bruenn, arrived quickly. He confirmed that Roosevelt had suffered a cerebral hemorrhage. “It was a bolt out of the blue,” Bruenn later observed, “A good deal of his brain had been damaged.”

Millions mourned the unexpected loss of this great leader. Americans who lived en route from Georgia to Washington D.C. were able to pay special honor to their beloved FDR as the train carrying his coffin made its way from Warm Springs to the Capitol. The coffin’s final stop was Hyde Park, where Roosevelt was laid to rest in his mother’s rose garden, just as he had wanted.

Twenty days after FDR’s death, Hitler killed himself. One week later, Germany’s military leaders surrendered to General Eisenhower. On May 7, 1945 the war in Europe was finally, officially over.

Helen Keller beautifully articulated the sadness that so many felt upon the loss of Franklin Delano Roosevelt:

It was as if the beneficent luminary in whose rays civilization was putting forth new leaves of healing for all people was seemingly extinguished forever.... All at once, a guest… came straight to us from the telephone with the tidings of the President’s death. Everybody grew limp and silent. Soon church bells were tolling, and flags were at half-mast.

Though FDR passed away in 1945, Eleanor Roosevelt carried his legacy forward until the day she died, working courageously towards fulfilling their shared hope of a global commission on human rights.

Postscript – Japanese Internment Camps

All humans are fallible, capable of good and bad decisions. FDR was not exempt. Under ailing health and unbelievable pressure, FDR and his Cabinet ordered all Japanese Americans be sent to remote camps after the attacks on Pearl Harbor. This might have quelled national paranoia and enabled the investigative arms of the government to assess whether Japanese Americans posed a threat to national security, but ultimately it deeply hurt Japanese American families, and marks a tremendous human rights grievance under FDR’s leadership.

Similarly, after the attacks of September 11, 2001, many Americans looked with distrust at anyone in the country who appeared to be Middle Eastern or Muslim. Was it patriotism or paranoia?

Joy Hakim, Freedom: A History of Us (New York: Oxford University Press, 2003) 292.

Goodwin “Person of the Century”.

Lorenzo Milam, The Cripple Liberation Front Marching Band Blues (Mho & Mho Works, 1983) page unknown.

Kim E. Nielsen, The Radical Lives of Helen Keller (New York: New York University Press, 2004) 79.

Goodwin “Person of the Century”.

Franklin D. Roosevelt, F.D.R. Lives On: The Great Speeches of President Roosevelt, Ed. Michael B. Landis (Washington D.C.: Presidential Publishers, 1947), 35.

Speeches that Changed the World (London: Smith-Davies Publishing Ltd, 2005) 101-102.

Goodwin, “Person of the Century”.

Goodwin “Person of the Century”.

Goodwin “Person of the Century”.

Doris Kearns Goodwin, No Ordinary Time: Franklin and Eleanor Roosevelt: The Home Front in World War II (New York: Touchstone, 1994) 602.